The Igorot Village of Coney Island

Page 5 of The Brooklyn Times from May 12, 1905. Note the Bontoc person in box 6 of the image. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library.

In the Spring of 1905, New York newspapers regaled readers with the summer’s upcoming spectacles and attractions to be hosted at the city’s amusement center, Coney Island. But one particular “exhibition” caught the attention of most New Yorkers. On May 9, 1905, The Standard Union reported: “A band of fifty-one Igorrotes from the Bontoc Province, Island of Luzon [Philippines] is coming across the continent, bound for Luna Park, where they will provide an attraction entirely different from anything ever seen in a Coney Island amusement resort.”

Fifty-one Filipino natives from the Bontoc region of the northern Philippine Island Luzon were exhibited at Coney Island amusement parks, Luna Park, and Dreamland Park in 1905. The community was referred to as the Igorrotes or Igorot, a term loosely used to describe multiple ethnicities from this region of the Philippines.

Publicized as the Igorot Village, the exhibition was touted to educate the American public on the country’s new territorial holding following the imperial conflicts of the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine-American War (1899-1902). Although the United States declared war in the Philippines a victory, fighting continued until 1913.

The exhibition was headed by showman Truman Hunt, who employed the Igorrotes or Bontoc people to build mock villages and perform choreographed forms of their routines and customs from the Philippines. The village brought the eyes of New York onto Coney Island that summer. The press looked to Igorrotes for the next sensationalized story, masses of onlookers came to view America’s “new ward,” and a president’s daughter visited, reaffirming the United States’ stance on the Philippines. With their culture exploited for public entertainment, the Igorrotes’ time on Coney Island was America’s Imperialist fantasy on display.

Coney Island's Igorot Village was not the first display of indigenous peoples. Human exhibitions had a longstanding tradition in the United States and were often the cornerstone of nineteenth and early twentieth-century fairs and circuses. These displays enforced a racial interpretation of hierarchy, expansion, and exclusion. In 1904, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition hosted in St. Louis, Missouri, provided the United States with a venue to demonstrate its new role as an imperial power. At the instruction of former Governor-General of the Philippines William Howard Taft, a forty-seven-acre “Philippine Reservation” was built on the fairground. Drawing thousands of visitors, the exhibition's notoriety further the U.S. government’s justification for occupation. But it gave showpeople like Truman Hunt, supervisor of the Igorot Village in St. Louis, a new means to capitalize on a captivated public.

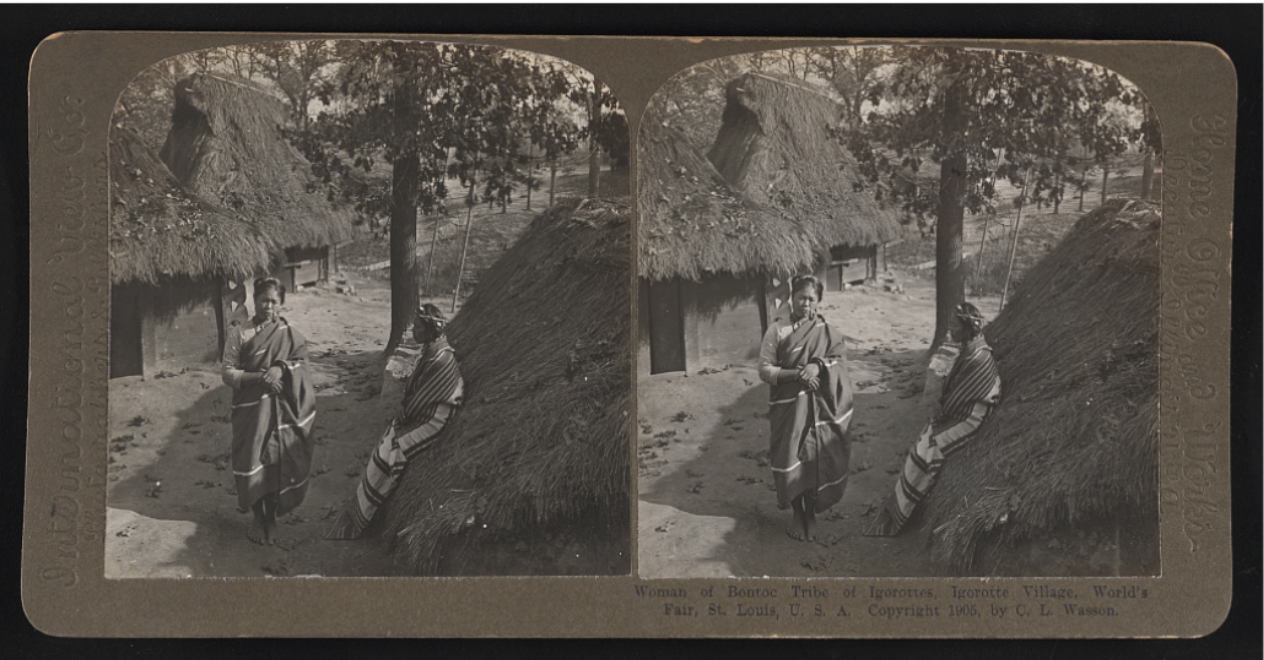

Woman of Bontoc tribe of Igorottes, Igorotte Village, World's Fair, St. Louis, U.S.A., 1905. Courtesy of the Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/resource/stereo.1s47814/

Hunt returned to the Philippines in December 1904 following the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. During this trip, Hunt recruited Filipinos to travel to the U.S. under his new amusement venture, the Igorot Exhibit Company. A complete understanding of business agreements between the Bontoc people and Hunt remains unclear. However, what is known is Hunt and the Filipinos agreed to a monthly wage of fifteen dollars each, plus all proceeds sold from souvenirs of their creation.

The Bontoc people arrived in New York City in mid-May 1905, after the official start of Coney Island’s summer season. Their arrival was delayed by the death of two community members following their Seattle exhibition two weeks earlier. Despite the circumstances, the press quickly took to reporting their arrival. In an imperial tone, The Brooklyn Times wrote: “These are the wildest people Uncle Sam has ever had anything to do with.” The Bontoc people entered Coney Island’s Luna Park on May 15th. Behind schedule, they were quickly prompted by Hunt to begin construction on the exhibition, which would take up twelve acres of the park. Five days later, in a second grand opening celebration, the Igorot Village officially opened to the public.

The Igorot Village was located on the Northeastern end of Luna Park. Map of Coney Island, 1905. Courtesy of the Center for Brooklyn History https://mapcollections.brooklynhistory.org/map/maps-of-coney-island-1905/ https://mapcollections.brooklynhistory.org/map/maps-of-coney-island-1905/

Coney Island’s Igorot Village continued the narrative of sensationalized American imperialism. The American public saw the need for U.S. colonization through exaggerated displays of “primitive” Filipino culture. And from his experience in St. Louis, Hunt understood this notion drew crowds. He decontextualized aspects of the Botonc peoples’ culture through clothing, built architecture, and performances on display in the village.

Ever the showman, the village was decorated with spears and skulls, which Hunt told visitors were human remains of the Botonc people’s enemies from the Philippines. But in actuality, they were animal remains. Hunt also had the group continuously construct and deconstruct structures based on Filipino architecture so parkgoers could see them involved in constant activity.

Playing along with the public’s imagination, Hunt directed the group to perform mock hunts and ceremonies such as weddings or the “Bontoc war dance.” Hunt also introduced the “witch doctor” role in the group. A Coney Island souvenir guide noted the misconstrued position as one of the village’s highlights: “Among them are two war chiefs and a witch doctor.” In the most damaging of these performances, Hunt drew on the popularity of the staged “dog feast” in St. Louis and made this a key feature of Luna Park and Dreamland’s Igorot Villages.The New York Press, often in collaboration with Hunt, added to the sensation surrounding the Igorot Village. In July 1905, a Brooklyn newspaper article headlined: “Igorrotes Fight Hard After a Feast of Day: Fox Terrier And Russian Wolfhound Stolen and Cooked by The Band.” In a dramatized account of Luna Park’s animal caretakers and the Igorrotes, the story suggests the group stole animals for a “dog feast.” Although interpreter Julio Balinag denied the accusation, articles like this would be commonplace in the summer of 1905. The overdo of the press generated interest in the exhibition, but in the same breath, contributed to harmful characterizations of the Igorrotes’ culture.

The photo-op of the summer came when President Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, visited. No stranger to the press, Alice Roosevelt, known for her rebellious persona, served as an extension of her father’s image. The Brooklyn Citizen reported, “[She] chatted with them [the Igorrotes] for five minutes, talking part Spanish and part English.” Her short visit served in part as a reminder of the Roosevelt administration’s stance on the Philippines. To which President Roosevelt wrote: “If white people were morally bound to abandon the Philippines, we were also morally bound to abandon Arizona to the Apaches.” Shortly after, Alice Roosevelt and her father’s presidential successor, William Howard Taft, embarked on a diplomatic tour of Asia, which included a stay in the Philippines.

Alice Roosevelt and William Howard Taft during their diplomatic tour of Asia in 1905. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_collection:sova-fsa-a2009-02?q=FSA+A2009.02&fq=object_type%3A%22Collection+descriptions%22&record=1&hlterm=FSA%2BA2009.02&inline=true

Under Hunt’s employment, the Bontoc peoples’ labor and culture were exploited for public entertainment. The group worked under grueling conditions. They were directed to perform for long hours, provided with an insufficient diet, not allowed to leave the village, and did not have proper living quarters. The community raised workplace issues with Julio Balinag, but management met their grievances with condescension.

The press caught word of rising tensions, which Hunt used to his advantage. In reporting on the group's move from Luna Park to Dreamland Park in August 1905, the New York Times wrote: “A difference in opinion in culinary matters between Thompson & Dundy of Luna Park and twenty-five little Igorrotes… has temporarily dissolved the contract between these two parties.” The article stated the group’s disagreement was not about working conditions but rather about having more access to dog meat. Drawing on the caricature of culture the exhibition created, Hunt turned a lucrative deal with the competing Dreamland Park into a publicity stunt.

Towards the end of Botonc peoples’ time in Coney Island in September 1905, Hunt’s unscrupulous nature began to catch up with him. As the Igorot Exhibit Company continued to travel, the Botonc people reported Hunt’s actions to the police in three cities. A U.S. government investigation report, in which Julio Balinag played a major role, stated that Hunt had defrauded and owed the community an estimated USD 15,000 for fifteen months of work. Hunt served eight months for charges related to the handling of the Igorot Exhibit Company.

The lack of historical records doesn’t allow us to fully understand how the Bontoc people felt after the events of Coney Island or their lives afterward. But the Igorot Village’s legacy remains— a spectacle of American imperialism at the expense of a people’s exploitation.

Theresa DeCicco is a public historian and museum educator based in New York City. Her current research focuses on the Filipino-American experience in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.